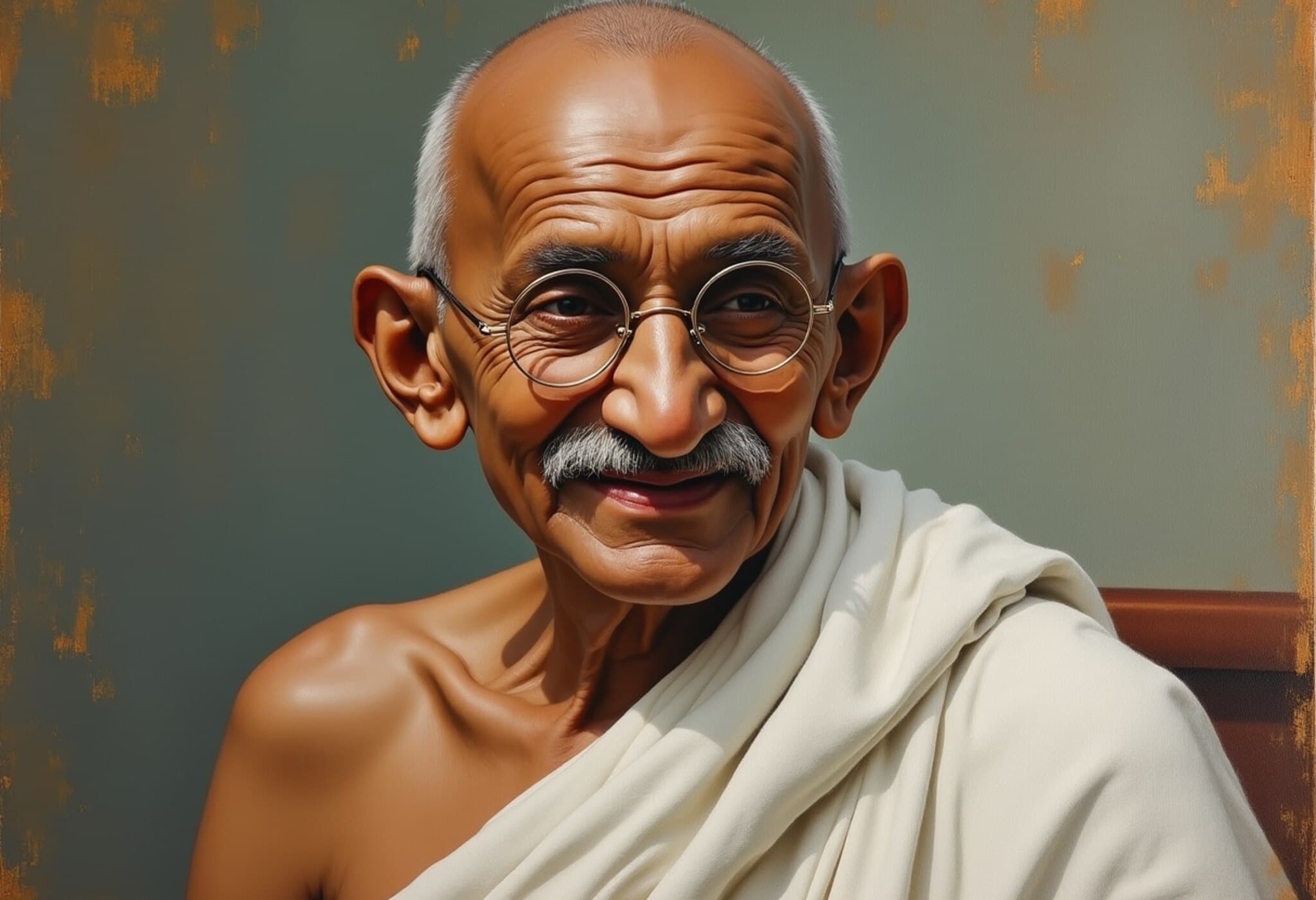

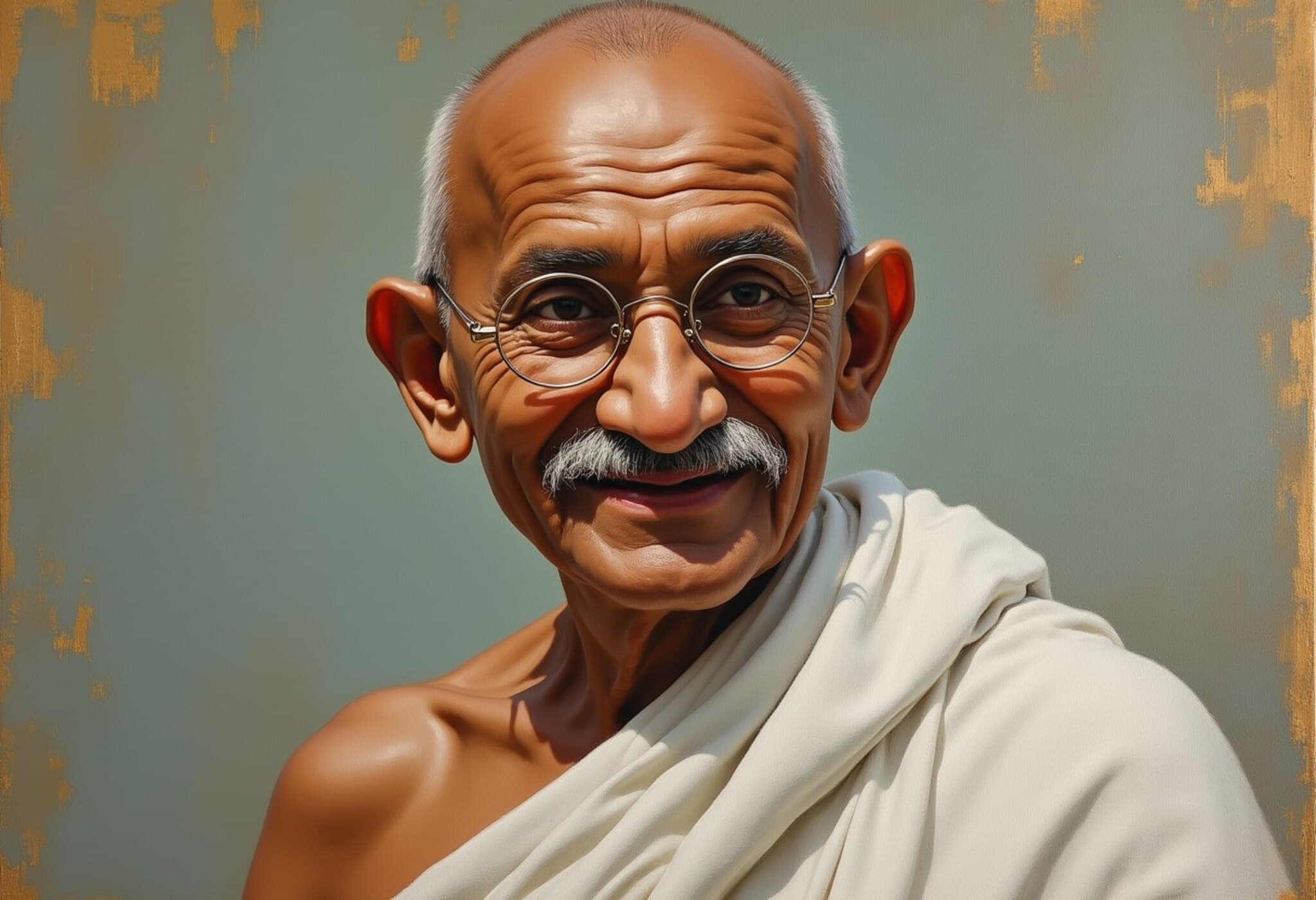

Rare Mahatma Gandhi Oil Portrait Breaks Auction Records

A singular piece of history recently captured the art and auction world’s attention—a rare oil portrait of Mahatma Gandhi, believed to be the only one he ever personally sat for. Painted by renowned British artist Clare Leighton in 1931, the work beautifully encapsulates Gandhi’s iconic presence during a pivotal moment in India’s struggle for independence. The piece sold for an astonishing ₹1.63 crore (approximately £152,800 or $204,648) at a prestigious Bonhams auction in London, more than doubling its original estimate.

A Moment Frozen in Time: Gandhi’s Visit to London

The portrait was created during Gandhi’s 1931 visit to London, coinciding with the Second Round Table Conference. This conference was critical, focused on negotiating India’s constitutional future under British colonial rule. Clare Leighton, primarily celebrated for her masterful wood engravings, was among the rare artists granted the honor of painting Gandhi from life. Through the introduction from her partner Henry Noel Brailsford—a committed journalist and advocate for Indian independence—Leighton spent several mornings sketching Gandhi in his London residence.

The painting captures Gandhi in a contemplative pose: wrapped in his shawl, bare-headed, his finger mid-gesture as if mid-discussion—an intimate glimpse into his demeanor during such a charged period.

The Portrait’s Journey: From Exhibit to Auction Block

Initially exhibited in November 1931 at London’s Albany Galleries, the painting attracted significant attention, drawing Members of Parliament and prominent Indian leaders like Sarojini Naidu and Sir Purshotamdas Thakurdas, though Gandhi himself was not present. Writer Winifred Holtby vividly recalled Gandhi’s likeness in the portrait—highlighting the delicate complexity of his expression and stance—testament to Leighton’s skill in capturing more than mere physical form.

Gandhi’s secretary, Mahadev Desai, conveyed gratitude to Leighton in a letter shortly after, praising the portrait’s faithful representation. For decades, however, this historically significant artwork remained largely out of public view, residing in Leighton’s family after her death in 1989.

Notably, the painting suffered damage during a 1974 public display when it was attacked with a knife but was professionally restored by the Lyman Allyn Museum Conservation Laboratory. It resurfaced briefly in public exhibitions, including a 1978 showcase at the Boston Public Library.

Why This Portrait Matters in Today’s Context

Beyond its monetary value, this portrait is a vital cultural artifact. It offers a tangible connection to Gandhi's human presence at a time when political tides were shifting dramatically. For contemporary audiences, especially in India and among diaspora communities, the painting evokes deep reflections on colonial history, the sacrifices entailed in the independence movement, and Gandhi’s enduring legacy of peaceful resistance.

Furthermore, the artwork's resurgence in the auction spotlight invites questions about the preservation and public accessibility of important historical artworks. As of now, Bonhams has withheld the buyer’s identity and future plans for public display remain uncertain, highlighting ongoing challenges in balancing private ownership with cultural heritage.

Expert Insight: The Intersection of History, Art, and Memory

From a policy and cultural perspective, artworks like Leighton’s portrait underscore the importance of safeguarding national treasures that play crucial roles in collective memory. American institutions, for example, have long wrestled with policies to repatriate or exhibit historically significant pieces. In India’s case, mobilizing resources to acquire or exhibit such works could enrich public understanding and global appreciation of its freedom struggle.

Moreover, this sale underscores the robust international market for South Asian historical art, reflecting growing global interest but also the necessity for frameworks ensuring these artifacts remain accessible to the communities whose histories they represent.

Editor's Note

The sale of Gandhi’s only known oil portrait is more than just an art transaction—it is a poignant reminder of the enduring power of history captured through art. As this masterpiece moves into private hands, it raises vital questions: How do we ensure that such culturally significant works remain accessible? What responsibilities do collectors and institutions have in preserving and sharing our shared heritage? In an age where historical memory is often contested, this painting stands as both a symbol and a call for mindful stewardship of our past.