UK Broadens Controversial Deportation Policy Amid Crime and Overcrowding Concerns

In a significant shift aimed at addressing rising crime and prison overcrowding, the UK government announced it will expand its “deport first, appeal later” policy to cover nationals from 23 countries, including India, Canada, Australia, and Kenya, among others. This expansion marks a nearly threefold increase from the previous list of eight countries, intensifying debates around immigration, justice, and human rights.

Understanding the ‘Deport First, Appeal Later’ Policy

Originally introduced by the Conservative government in 2014 and reactivated in 2023, the policy allows for the deportation of foreign nationals convicted of crimes in the UK immediately after sentencing, without waiting for their appeals to conclude. The only exception is if the offender can demonstrate a credible risk of harm in their home country.

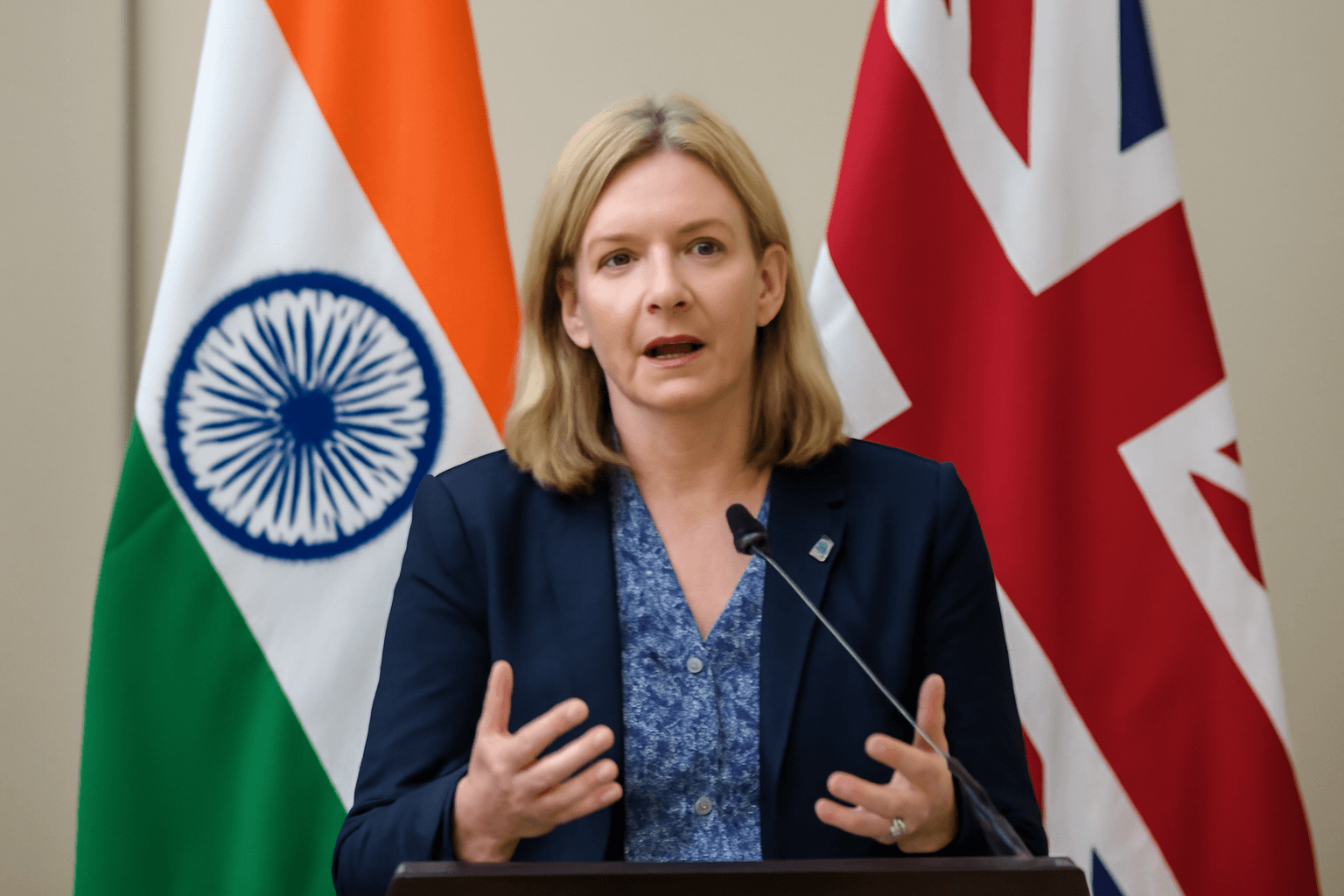

Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood highlighted the urgency of the move, stating that foreign offenders serving fixed-term sentences will now be removed from the UK swiftly, effectively blocking any chance of returning. However, individuals convicted of the most serious offenses—such as terrorism or murder—will serve their full life sentences domestically before deportation.

Government Rationale and Opposition Concerns

Home Secretary Yvette Cooper defended the policy as a necessary tool to curb the exploitation of the UK’s immigration system by foreign criminals who linger on long appeals, sometimes for years. She emphasized the government’s commitment to protecting communities and alleviating prison pressures.

Yet the policy remains contentious. Former Conservative Justice Secretaries Alex Chalk and Robert Buckland voiced serious reservations. Chalk warned that the policy risks turning the UK into a “magnet” for offenders seeking to dodge full justice, noting that some deported criminals—ranging from rapists to domestic abusers—might escape serving their prison sentences entirely if their home nations do not incarcerate them properly.

Legal and Practical Challenges

The policy’s legal foundation has been shaky. Courts previously struck down earlier versions of the scheme — notably the UK Supreme Court in 2007 ruled it unlawful for restricting a convict’s ability to present live evidence during appeals. Subsequently, the government introduced safeguards including video link testimonies to mitigate these concerns.

However, according to Ministry of Justice data, there is no guarantee that deported offenders will face equivalent prison time back home. This gap raises pressing questions about whether the policy truly serves justice or merely shifts responsibility elsewhere.

Impact and Regional Relevance

- Prison Overcrowding: The UK faces chronic overcrowding in its prisons, with foreign offenders constituting a substantial percentage. The policy seeks to ease this strain but its efficacy remains debated.

- India-UK Relations: Inclusion of India—a country with complex legal and prison systems—adds layers of diplomatic and logistical challenges. Ensuring that deported Indian nationals serve sentences fairly and humanely requires robust bilateral cooperation.

- Immigration Policy and Public Perception: This move may fuel anti-immigration narratives and impact broader immigration reforms in the UK, impacting communities from the Commonwealth who have longstanding ties to Britain.

Statistics Reflecting the Policy’s Reach

Since the Labour government took office in July 2024, the UK deported 5,179 convicted foreign nationals—a 14% increase compared to the previous year—underscoring an intensified focus on foreign offenders amid political and public pressures.

Critical Perspectives: Balancing Justice and Human Rights

The expansion of the “deport first, appeal later” policy underscores the ongoing tension between national security, immigration controls, and safeguarding legal rights. While politicians emphasize public safety and system efficiency, critics caution that expedient deportations risk sidelining due process and violating human rights standards.

Expert legal analysts point out the need for transparency, international cooperation, and mechanisms to monitor the treatment of deportees abroad. Without these, the policy could inadvertently foster prisoner rights abuses or create diplomatic strains.

Looking Ahead: Questions for Policy Makers

- How will the UK guarantee that deported offenders serve appropriate sentences and are not just displaced?

- What safeguards are in place to protect vulnerable individuals facing deportation, especially those citing risk of harm?

- Can expanding this policy sustainably reduce prison overcrowding without compromising justice?

- How will the UK address the political and societal implications of including key Commonwealth countries like India and Canada?

Editor's Note

As the UK tightens its immigration enforcement, the expanded deportation policy represents a critical juncture at the intersection of crime control, legal fairness, and international relations. While aimed at cracking down on foreign criminals, it raises profound questions around rights, rehabilitation, and the very nature of justice in a globalized world.

For readers tracking this evolving story, it is vital to stay informed about the emerging outcomes, bilateral dialogues, and legal challenges that will shape the policy's long-term impact on individuals, communities, and diplomatic ties.