On Tasmania’s rugged landscapes, vast native eucalyptus forests are being logged, raising ecological alarms among environmentalists. In the Huon Valley’s Grove of Giants, a 500-year-old eucalyptus stump remains, a stark reminder of centuries-old trees felled in the state’s logging industry.

Jenny Weber, campaign manager at the Bob Brown Foundation, highlighted the environmental loss, emphasizing the irreplaceable value of such ancient trees. Tasmania, boasting extensive forest cover uncommon in Australia’s usually arid environment, legally permits native tree logging. Yet this practice has significant ecological implications.

Statistics reveal Tasmania accounts for 18.5% of native tree harvesting nationally, notably higher than Australia's average of 10%. While other states like South Australia have long protected native forests and Victoria and Western Australia have banned native logging since 2024, Tasmania continues despite growing calls to halt the practice.

Public opposition is evident; over 4,000 people protested in Hobart, highlighting endangered species such as the Tasmanian devil and the critically endangered swift parrot—both reliant on old-growth eucalyptus trees for habitat. Charley Gros, ecologist and Bob Brown Foundation adviser, explained that the absence of tree hollows prevents breeding, threatening species survival.

Sustainable Timber Tasmania manages over 800,000 hectares of public forests, aiming to balance timber harvesting with conservation. The organization reports harvesting around 6,000 hectares of native forest annually—under 1% of managed land—and actively monitors endangered species to adapt forestry practices. Additionally, in 2023-2024, it sowed 149 million seeds to regenerate native forest areas.

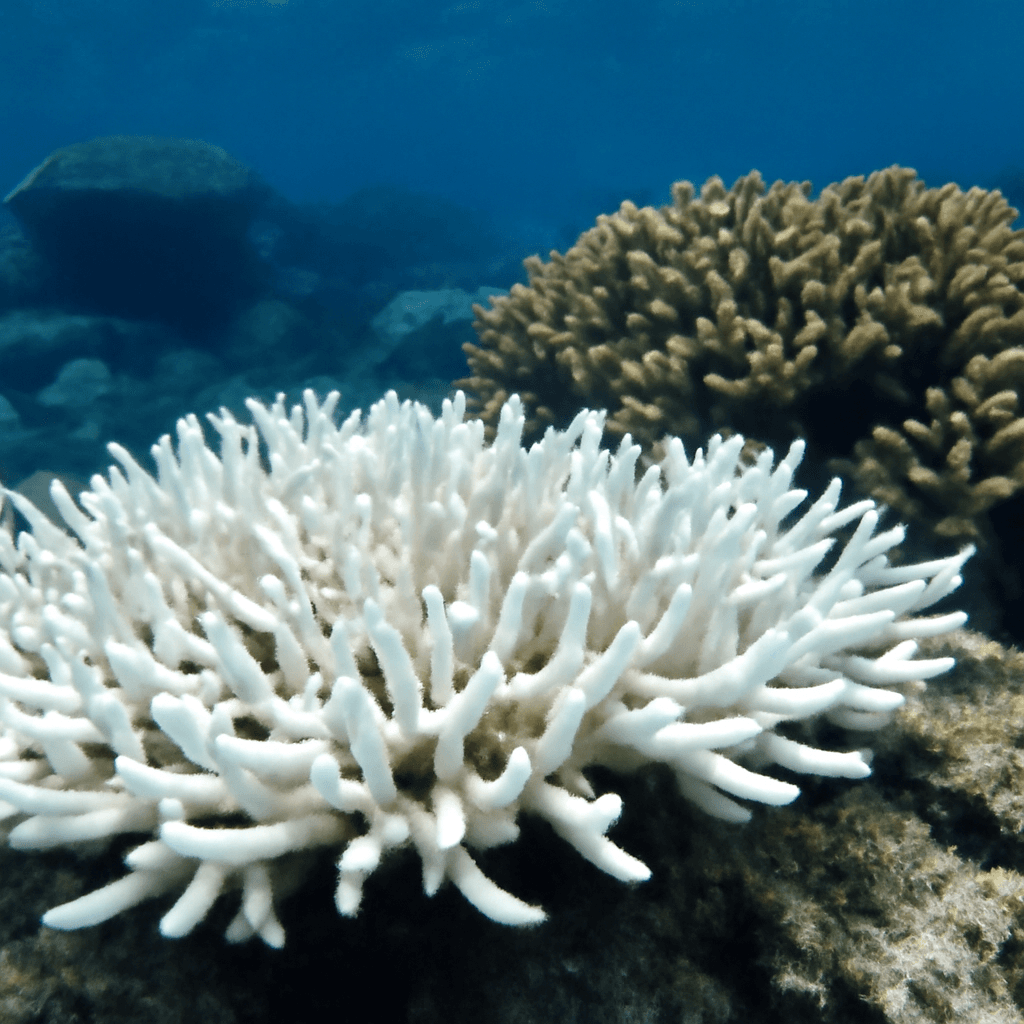

However, environmentalists question these efforts as significant portions of felled timber become export wood chips for products like paper and cardboard, contributing to ecological degradation. Moreover, forest clearing methods, including aerial incendiaries, damage residual ecosystems, producing toxic fumes.

Further controversy surrounds wildlife management during regeneration: animals such as wallabies and possums, which feed on new shoots, are reportedly culled to protect young eucalyptus growth meant for future logging. Critics also note that replanting focuses solely on eucalyptus, neglecting other indigenous species essential for a balanced forest ecosystem.

This ongoing conflict between economic interests and environmental preservation underscores the complex challenges Tasmania faces in managing its native forests sustainably.