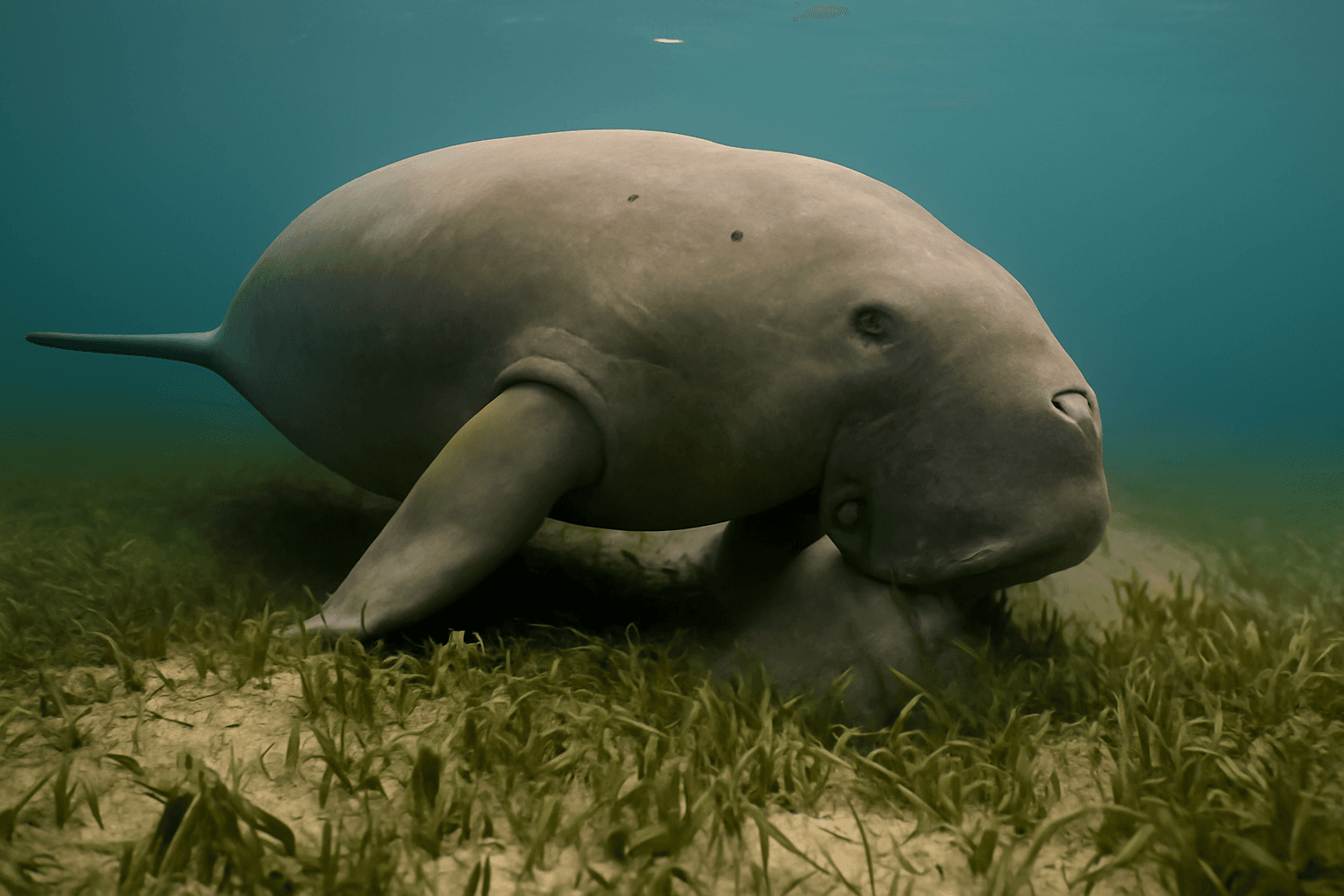

India’s dugongs (Dugong dugon), often referred to as the 'farmers of the sea,' once thrived across Indian coastal waters but now face critical threats that have reduced their numbers to an estimated 200 individuals. Their population and habitats have significantly diminished, making dugong conservation a pressing priority. May 28 marks World Dugong Day, highlighting the importance of protecting these unique marine mammals.

Dugongs are gentle, herbivorous marine mammals found primarily in shallow coastal waters where seagrass meadows flourish. Along the Indian coastline, dugongs inhabit warm waters around the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Gulf of Mannar, Palk Bay, and the Gulf of Kutch. These creatures depend on seagrass species including Cymodocea, Halophila, Thalassia, and Halodule for food, consuming up to 20-30 tonnes daily to meet their nutritional needs.

Unlike their manatee relatives, dugongs are exclusively marine, thriving in a few meters of water depth. They are typically solitary or found in small mother-calf pairs, with reproductive maturity reached around nine to ten years and a slow calving interval of three to five years. This slow reproductive rate limits their population growth to approximately 5% annually, making them vulnerable to environmental pressures and human activities.

Threats to Dugongs and Their Habitat

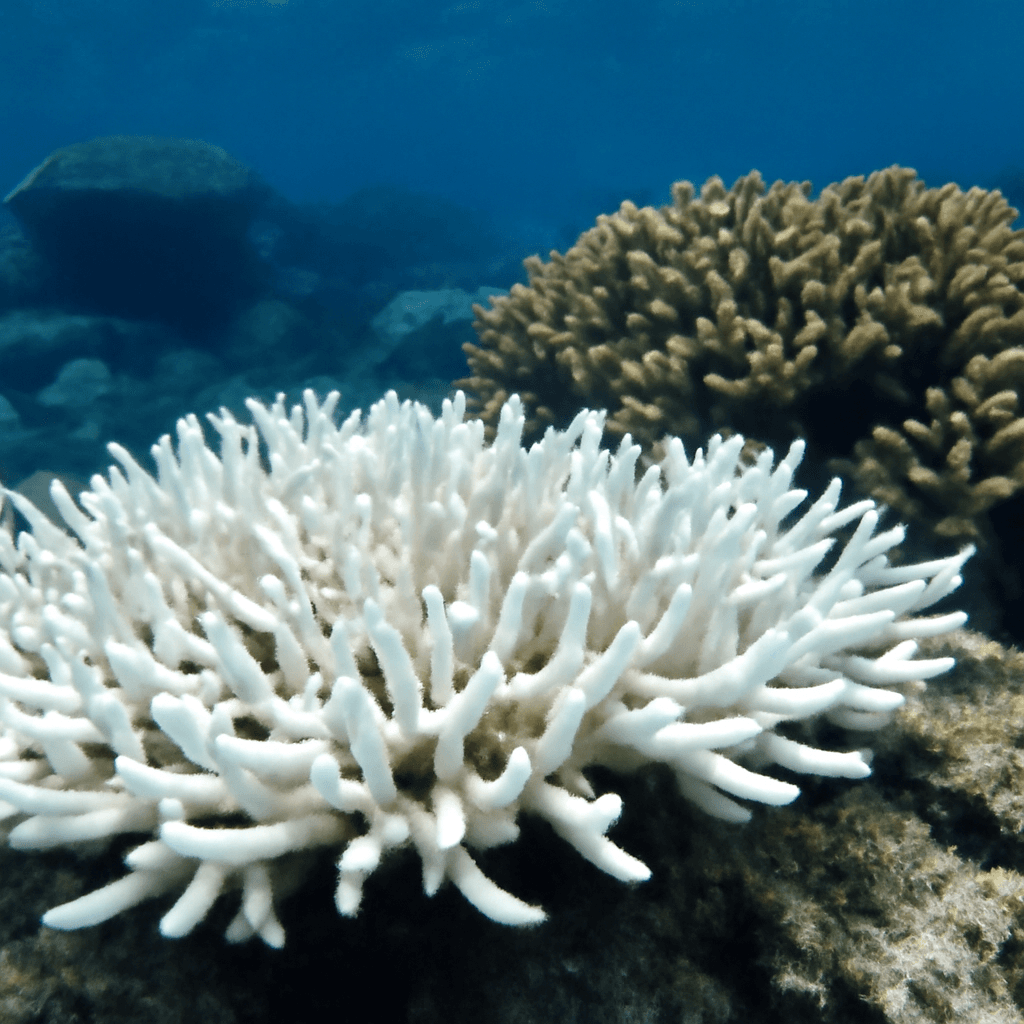

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies dugongs as ‘vulnerable’ globally and ‘regionally endangered’ in India. Their decline results from habitat degradation, accidental entanglement, illegal hunting, and pollution. Coastal development, including industrialization, port construction, dredging, and land reclamation, has devastated critical seagrass ecosystems. Concurrently, pollution from agricultural runoff, sewage, and industrial effluents further degrade water quality, threatening both seagrass and dugongs.

Modern fishing practices involving mechanized boats and harmful gear like gillnets and trawl nets increase the risk of accidental drowning for these air-breathing mammals. Increased boat traffic also poses collision hazards. Despite legal protection under Schedule I of India’s wildlife laws, poaching persists, especially in remote regions of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Conservation Efforts and Future Directions

India has taken significant steps to protect dugongs, including signing international conservation agreements and establishing the country’s first Dugong Conservation Reserve in Palk Bay, Tamil Nadu, covering 448.3 sq km with extensive seagrass beds.

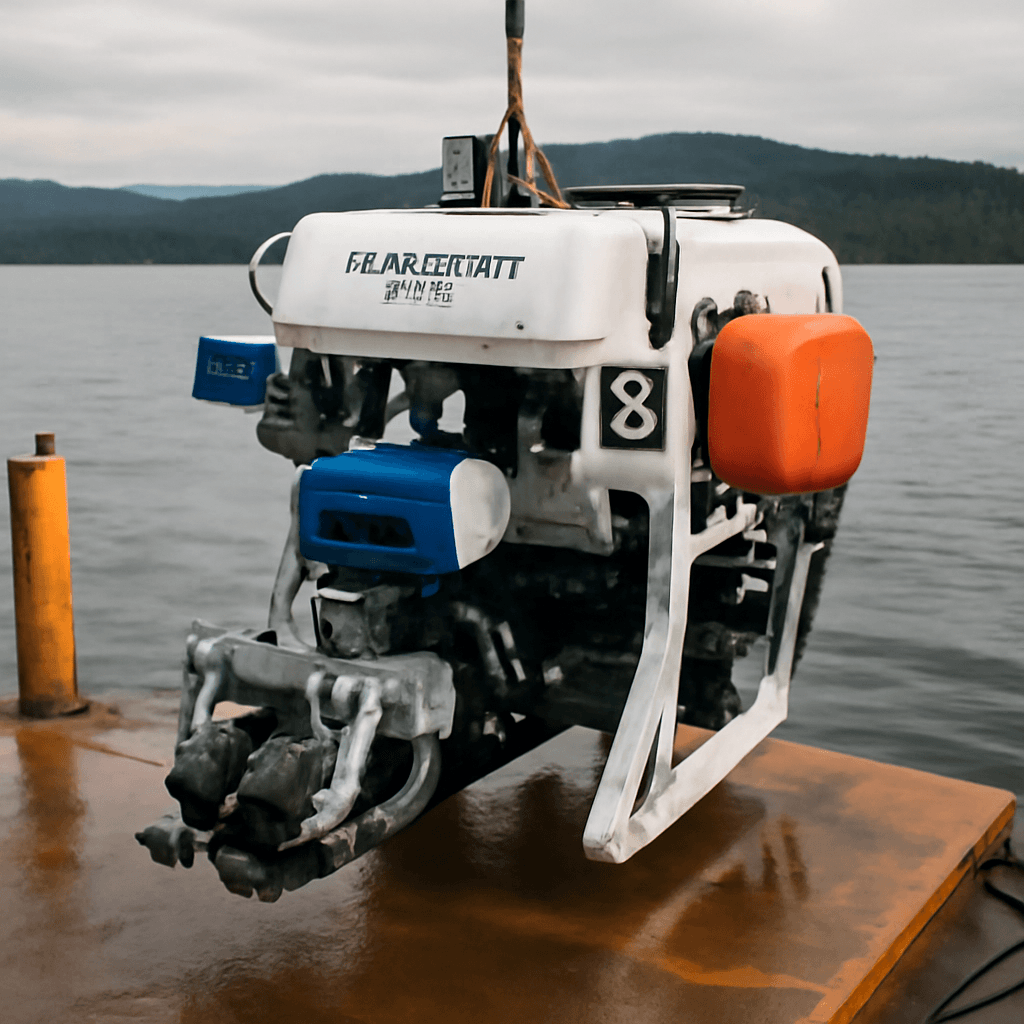

Research organizations like the OMCAR Foundation, Wildlife Institute of India, and Tamil Nadu Forest Department have long monitored these populations, contributing vital data for conservation planning. Experts emphasize the role of community engagement, sustainable fishing practices, and habitat restoration to support dugong survival.

Public awareness campaigns and community stewardship programs can empower local fishers to help monitor and protect seagrass meadows while promoting eco-tourism opportunities that benefit both dugongs and coastal communities.

The Importance of Seagrass Ecosystems

Seagrasses are flowering plants vital to coastal marine ecosystems. They stabilize seabeds, support diverse marine life, regulate carbon storage, and form the primary habitat and food source for dugongs. India's seagrass meadows, especially in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay, host the highest diversity in the Indian Ocean, covering over 516 sq km and sequestering significant amounts of carbon annually.

The preservation and restoration of healthy seagrass beds are fundamental to dugong conservation and broader marine biodiversity.

As Prachi Hatkar, an independent marine researcher, states, ‘Dugongs are gentle giants nurturing our seas, but their survival now depends on urgent actions to safeguard their fragile habitats from escalating threats.’ The future of India’s dugongs hinges on coordinated conservation efforts, sustainable development, and enhanced public awareness.

Priya Ranganathan, a doctoral researcher at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Bengaluru, contributed to this report.