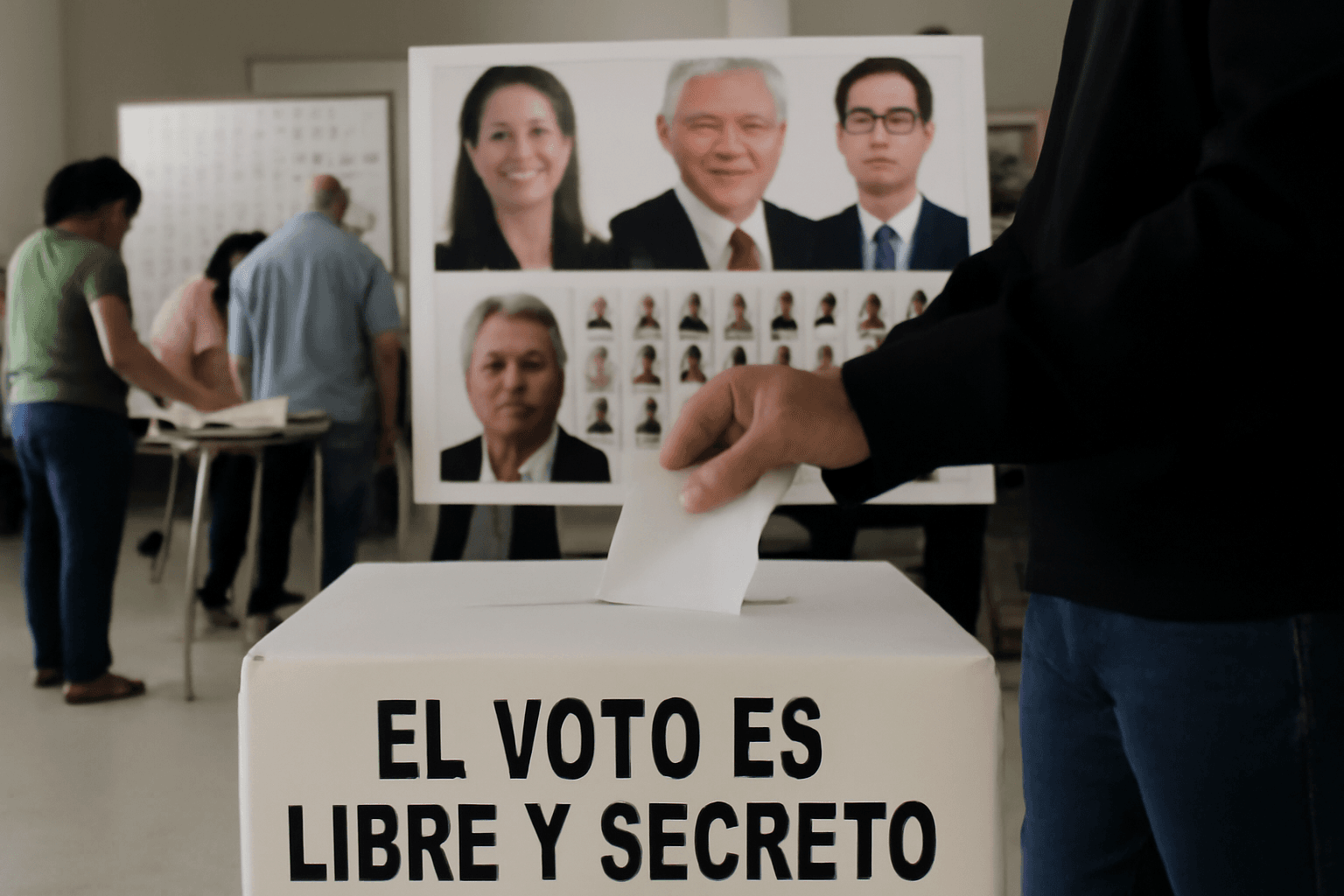

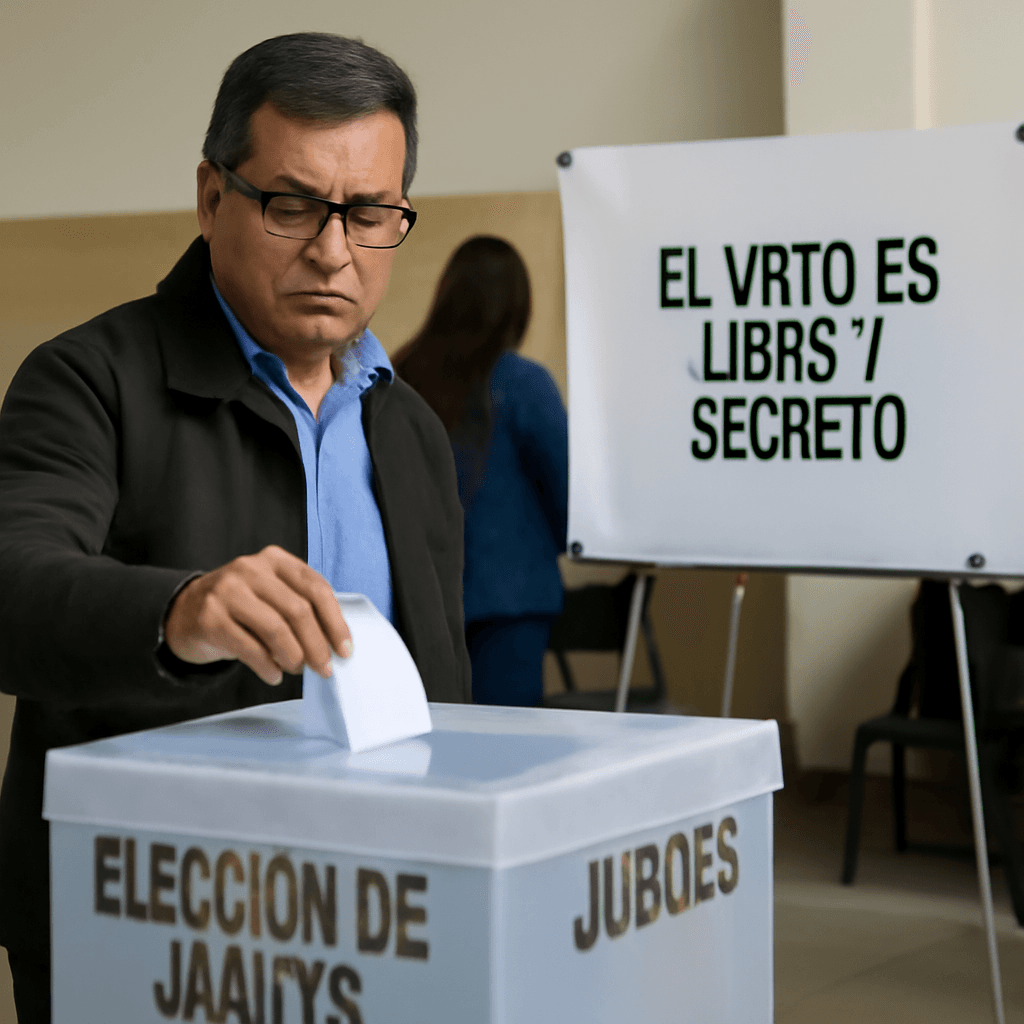

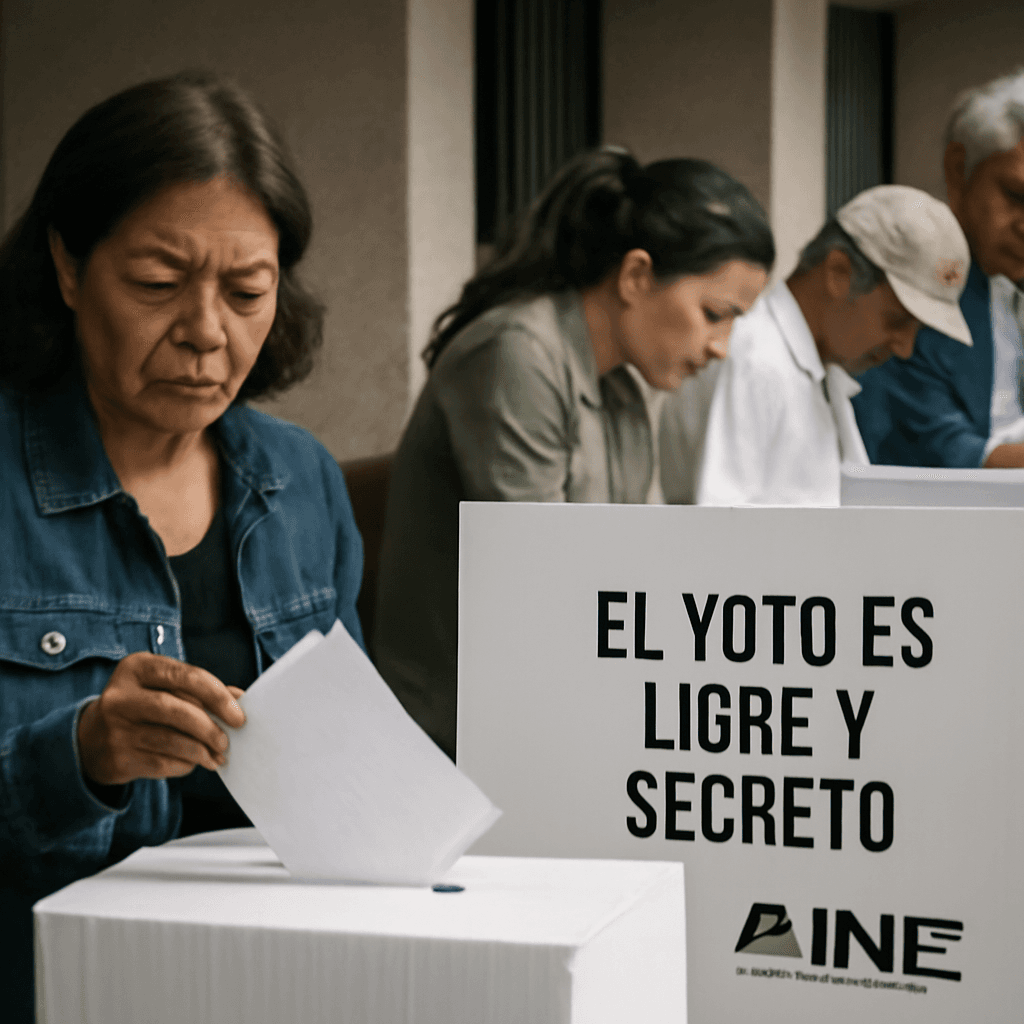

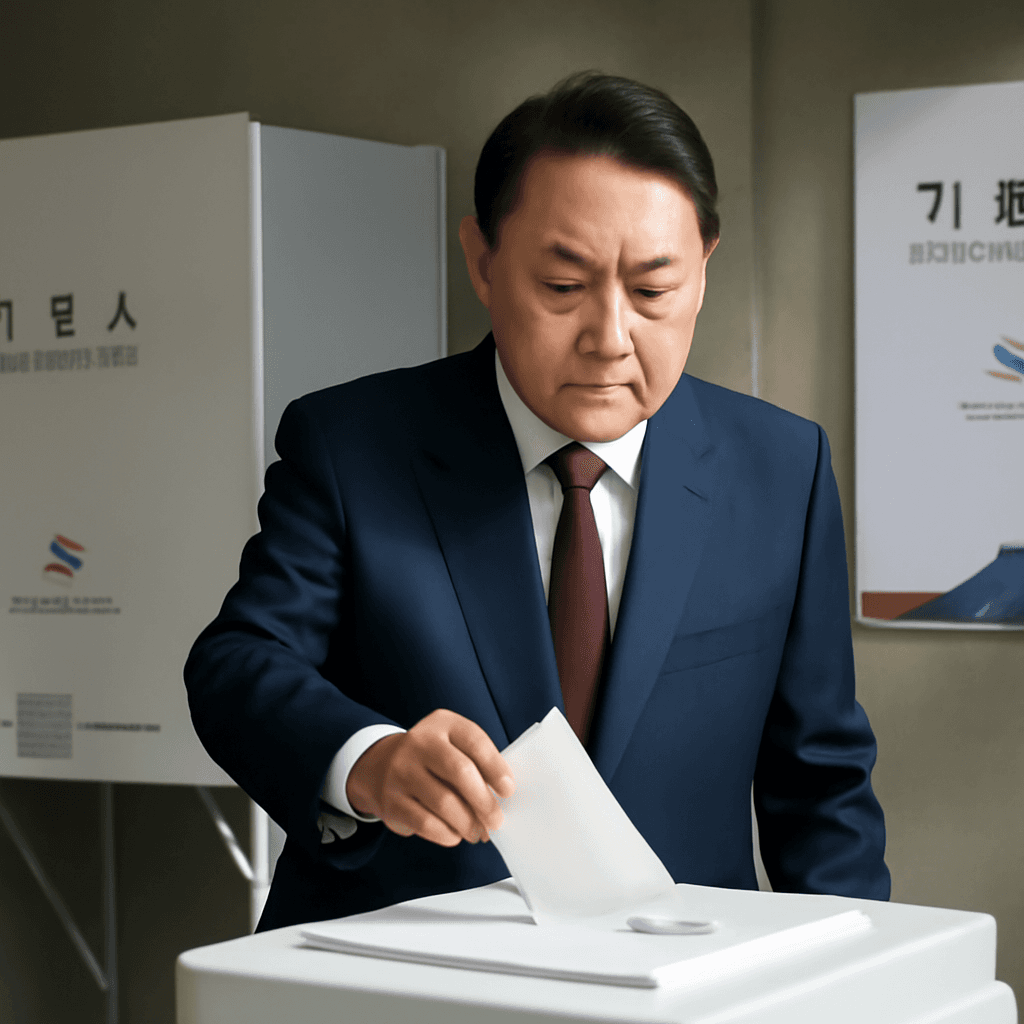

Mexico held its first-ever judicial elections on Sunday, sparking a national debate on whether this unprecedented move will bolster judicial accountability or undermine democratic checks and balances. The elections feature over 7,700 candidates competing for more than 2,600 judicial positions, including seats on the Supreme Court.

The judicial overhaul, championed by former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and continued by his successor, President Claudia Sheinbaum, aims to address longstanding judicial corruption and increase the judiciary's responsiveness to the public. Previously, judges and court officials were appointed based on merit and experience. Now, citizens directly elect judges, a method unique on the global stage.

Supporters argue that these reforms curtail the Supreme Court's power to obstruct presidential initiatives and enable greater public participation in the judiciary. Sheinbaum emphasized that this election marks a democratic milestone by entrusting judge selection to the Mexican people themselves.

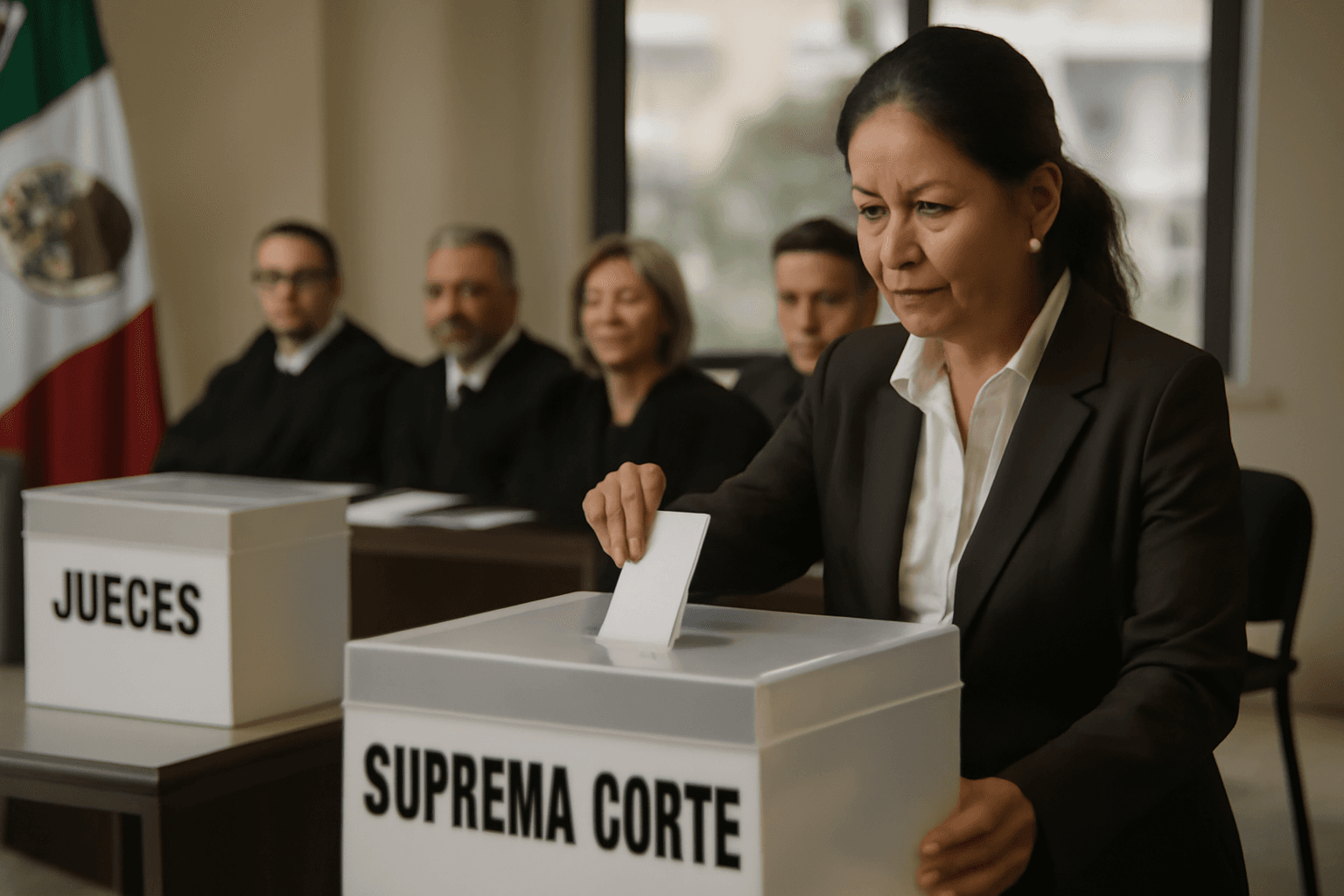

However, critics warn that the reform serves to consolidate power within the ruling Morena party and could weaken essential institutional checks. Many candidates are affiliated with Morena, and while party connections are officially barred during campaigns, political influence remains evident. A number of judicial staff and former judges staged protests opposing the reform, and international observers, including the Biden administration, expressed concerns about the potential erosion of judicial independence.

Concerns also arise regarding the impact on judicial quality and impartiality. Some candidates have controversial backgrounds, such as Silvia Delgado García, a former lawyer for notorious drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, who is running for a criminal court judgeship in Chihuahua. Observers worry this election may open the door for organized crime to further infiltrate the justice system.

The reform package was rapidly enacted last year, bypassing some lower-court injunctions and raising questions about the vetting process’s rigor, which included a lottery system to limit candidates. Mexico’s electoral authority is investigating reports of possible voter coercion through the distribution of campaign guides in certain regions.

Overall, the judicial elections arrive amid a complex political climate in Mexico, with concentrated executive power and persistent challenges from organized crime. Experts caution that this reform could destabilize the judiciary and detract from investor confidence, potentially affecting Mexico’s economic standing internationally.

As Mexico ventures into this judicial experiment, much remains uncertain about its long-term effects on the balance of power, anti-corruption efforts, and democratic governance.