For the first time, the West Nile virus has been identified in mosquitoes in the United Kingdom, marking a significant public health milestone linked to shifting climate patterns. The discovery was made by the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) during routine mosquito surveillance in Nottinghamshire’s marshlands along the Idle River.

The virus, which has traditionally been endemic to regions in Africa and West Asia, is now spreading into new areas in Europe due to rising temperatures. Experts consider climate change a key factor behind this northward expansion of vector-borne diseases.

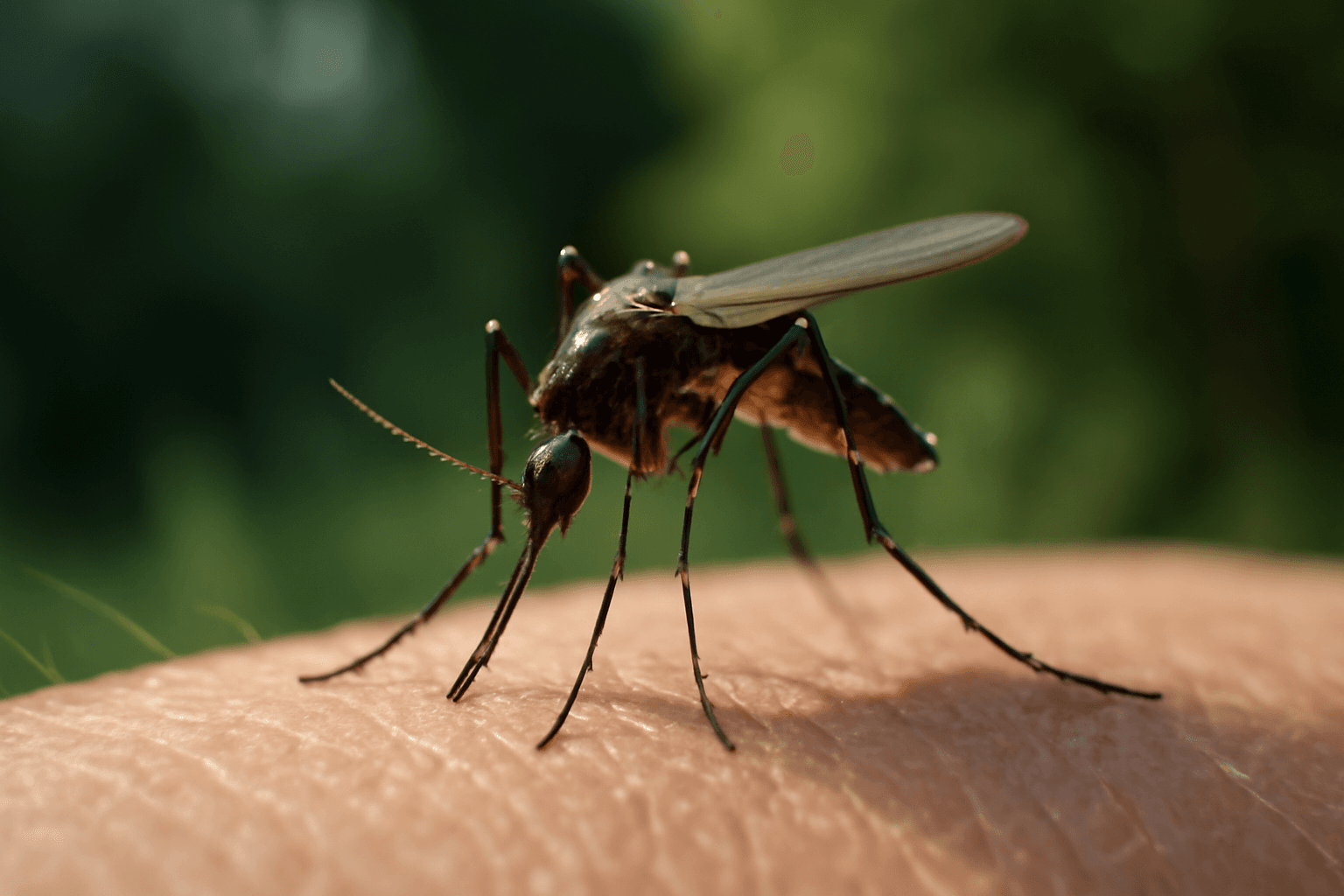

West Nile virus primarily circulates among birds, with mosquitoes acting as vectors that can occasionally transmit the virus to humans through bites. Although up to 80% of human infections are asymptomatic, severe cases involving encephalitis can result in brain injury or death. Notably, the virus does not spread directly between humans but can be transmitted through blood transfusions, organ transplants, pregnancy, or breastfeeding.

Dr. Arran Folly, an arbovirologist leading the APHA surveillance program, described the finding as "part of a wider changing landscape where mosquito-borne diseases are expanding to new areas in the wake of climate change." Warmer temperatures accelerate the virus’s replication within mosquitoes, making transmission more likely. For instance, at 15°C, the virus takes months to reach infectious levels, typically longer than a mosquito’s lifespan, whereas at 30°C, this process can occur within two to three weeks—well within a mosquito's average lifespan.

While no human cases of West Nile virus have been reported in the UK yet, researchers caution that continued warming could create conditions conducive to local outbreaks. Dr. Paul Hunter, a medical microbiology and virology expert, explained that a sufficient density of infected birds and mosquitoes, combined with prolonged warm weather, would be necessary for sustained transmission cycles.

The virus’s arrival in the UK is believed to have involved migratory birds infected elsewhere, underscoring the complex ecological factors underlying its spread.

This detection highlights broader concerns as climate change drives the appearance of diseases in regions without previous history of such infections, signaling evolving challenges in public health management and vector control strategies.